A Brief Description of My Process

There are no fixed rules, and I don’t always do it this way, but I usually begin a drawing by laying out a selection of a hundred or more patterned scraps, whatever appeals to me at that very moment, from boxes of hundreds of fragments of fabric, cut out before & during my work on each drawing, each scrap with fusible, an archival heat-sensitive adhesive, attached to its back — on a makeshift 4’ x 8’ table set up for the occasion.

It takes hours or even days of manipulating the scraps on another table covered with silicon release paper to rough out a figure or figures or partial figures or a head. Very often I must look through my boxes of prepared scraps to find something else or even cut new pieces from one of hundreds of fabrics I store in labeled boxes as well as in my head.

When I’ve taken the figure or figures or head as far as I can and it still interests me, I use an iron to fuse the scraps together. Then from among my boxes of fabrics, variously categorized, I look for a fabric to use as a ground. The ground itself may need substantial changes as the drawing progresses.

To provide weight & substance for all the sewing to come, I first fasten the ground fabric to raw canvas or linen with more fusible, then fuse the roughed-out imagery to the fabric-canvas ground. At this point and even immediately afterwards, when I sew around each scrap to hold it in place so that I can wad it up to fit under the sewing machine without all the little bits falling off, my drawings could be regarded as pure collage.

But this is only the beginning of a long process of sewing-into. Sewing/drawing is the essential transformative agent, an uncanny truth-teller. I stitch into the scraps and the ground with either a Consew 2033R or a 2053R industrial zig-zag sewing machine, using free-motion embroidery to draw lines and lay in areas of solid or scumbled color. By this means alone, I create transitions, unify disparate elements, carve out space, model form, and otherwise meld the variously patterned parts into a compelling whole. My sewn drawings and sewn books are artifacts of this process.

Because I make decisions on the fly, my eyes in shatterproof close- work glasses six inches from the needle, I start and stop sewing many times during an hour. I sew a little, cut the threads, look at what I’ve done, sew a little more, cut the threads, sew some more, stop and look again, cut the threads, change thread color and possibly also bobbin color, resume sewing, and so on. Each separate sewn passage has a long thread at the beginning and another hanging off the end of it, as well as a set of bobbin threads on the back of the work. After an hour of sewing, so many threads are hanging off the surface of the drawing that I can no longer see what I am doing and have to stop sewing. It takes about an hour, using a needle, forceps, and jeweler’s pliers, to draw the threads back one by one. It takes another hour, again using forceps, to tie the threads off and then to trim the excess with thread snips. Although drawing the threads back and tying them off is contemplative time for me, I work as fast as I can.

Things have to be neat front and back because I never know when revisions will require the undoing of large or small parts of a drawing. I can’t pick out the stitches if I don’t know where they are. My sewn drawings and sewn books take so long to make because I usually don’t know what they are going to look like until they are well under way, and even when I do, there are surprises until almost the end. But all I have to know is what to do next. The process does all the heavy lifting. I don’t have to imagine anything, just pay attention to what is happening under my hands and respond to it.

New Work With Embroidered Text

In March of 2013, I was awarded a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant that enabled me to buy a computerized embroidery machine, specialty threads, stabilizers, and CAD software, along with a Windows-based laptop to manage the software. I also hired someone to construct a seven-foot-long table on wheels from repurposed materials, to hold all of the above. I needed the software to create text files for the embroidery machine to stitch various typefaces, so that my books and drawings would have legible text suited to their imagery and intent, instead of approximate lines of text that I pieced together from whatever words I could find on printed fabric, cut out, and sew into place.

I had recognized how important the embroidery machine and its associated software could be to my art making almost two years before, when I first found out about them. My work was already machine-based. Since 2002, I'd drawn with an industrial zigzag sewing machine, my foot on the treadle, my nose six inches from the moving needle, making decisions on the fly, doing, undoing, and redoing over days and weeks to construct drawings and books that since 2009 featured original text as well as imagery. But having discovered a machine that would embroider text, I couldn't afford to buy it until the Pollock-Krasner Foundation provided the funding. And so I've just begun, but the first three drawings to incorporate embroidered text are notably speculative and word-filled. They are also more literary, performative, and lucid than previous drawings. Knee Deep in a Sea of Tears is like a page from a book of fairy tales. A Foreign Affair is a short story. Fighting Words is like something on Reality Television.

Meanwhile, something else happened that was entirely unexpected. As soon as I realized that the embroidery machine and software offered, in effect, a way to publish in my own medium, I found a new voice. I began writing short pieces to be machine-embroidered, then integrated, refined, and finished on my industrial zigzag machine—pure text pieces, with occasional illustrations—sewn broadsides! I have already made a considerable number of them, each one different from the next, as speculative as my books and drawings. They comprise an entirely new and growing body of work. I hope to construct my first book using embroidered text before the end of the year. I am already writing for it.

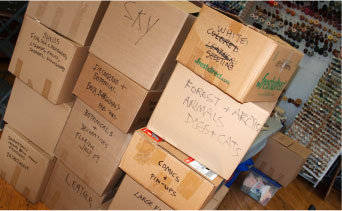

Boxes of Fabric

I have over seventy boxes of fabrics. At first I put them on shelves and shoved them under tables. When I ran out of room, I began stacking them up. I rarely buy more than a yard at a time, but I am always looking, in discount fabric stores, quilters’ catalogues, on the street, and in used clothing stores. Friends and acquaintances give me fabric, trim, and buttons. Sometimes I think that I should write on my forehead: STOP ME BEFORE I BUY MORE FABRIC! But sometimes I think that I should write STOP ME BEFORE I BUY MORE THREAD!

I look for and buy fabric everywhere I go, but since I live in New York City, I do most of my looking and buying locally, sometimes on the Lower East Side, Broadway below Canal, or in Queens or Brooklyn, but usually in what remains of the Garment District, from 40th Street down to 36th St., between 7th and 8th Avenues. I buy thread at Sil on 38th St. ( threadus.com / Sil Thread Inc ) and at Steinlauf & Stoller on 39th St. ( www.steinlaufandstoller.com) which also sells everything else a sewer might need. The kind people at S & S know who I am and what I do, but otherwise, I’m in stealth mode—not on purpose, but just because most people who buy thread, fabric, buttons, trim, sewing machine oil, and so forth, are not making art out of it.

Thread Storage Unit

Even though there are hundreds of spools and cones in my thread storage unit, I never have enough thread. There’s always a particular green or brown or red in a fabric that I can’t find a match for or cones of an uncanny yellow and a sublime blue-green that I discover in a bargain box, leftovers from a defunct garment factory. I even have some thread on wooden spools from my mother’s sewing box, still perfectly good after all these years. At first I put up racks to hold my spools of thread and kept my cones in a cardboard box. But I gradually ran out of room. So I designed a big thread storage unit and had it built. It’s already more than half full.